Roy Lichtenstein’s Comic Book Paintings

Table of Contents

1. Introduction: “I Can See the Whole Room"

2. Roy Lichtenstein’s Education and Early Work

3. Look Mickey!

4. Context: Comics and Pictorial Media in America

5. Context: Lichtenstein and the 1960s Art World

6. Lichtenstein’s Pop Art Technique

7. Mechanical Reproduction: Warhol/Lichtenstein

8. Transience: Rosenquist/Lichtenstein

9. Ways of Seeing: Ruscha/Lichtenstein

10. Seeing Lichtenstein’s Comic Book Paintings

11. Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Introduction: “I Can See the Whole Room"

Figure 1. Roy Lichtenstein, I Can See The Whole Room!... (1961)

I Can See The Whole Room!...(1961) (Fig. 1) is a part of the early Pop Art oeuvre of Roy Lichtenstein (1923-1997), coming at a time when he found that he could use the simple, direct imagery of American comic book art to convey complex ideas about vision and perception.

I Can See The Whole Room!... is most noticeably a reference to, and a piece of, a comic book. The simplified face, the flat color, the speech bubble, all hallmarks of comic book illustration that have become symbols of comics. The painting is also a visual pun or a humorous comment on art. If the peephole were closed we would be left with a plain black canvas, perhaps a reference to abstract and color field painting. The man’s exclamation that he sees “nobody” can be a good-natured jab at the viewer who is certainly somebody looking at the painting just feet from his hypothetical view, but the viewer could just as well be “nobody.”

I Can See The Whole Room!... is a painting about seeing: the man looks through the peephole and the viewer looks back at him. A comment is made on the ways in which we see and perceive this painting while it is looking back at us. The peephole can seem to refer to a shutter, a primitive photographic mechanism or a camera obscura, the idea of viewing through a mechanical device. The idea of being able to see to the “other side” of the painting also references the Renaissance idea of a painting as a window one looks through to view a scene. The “scene” Lichtenstein shows us is flat and unconcerned with naturalistic interpretation, denying the painting as a “window,” but the figure depicted still claims to see a room which we assume to be ours but cannot be because the viewer certainly is present upon viewing the painting.

Roy Lichtenstein’s Education and Early Work

Lichtenstein often credits his understanding of “what art is all about” to his teacher and mentor Hoyt L. Sherman, whose presence was so prevalent in Lichtenstein's life and work that years later the artist named his son David Hoyt Lichtenstein and also donated a large sum of money to the creation of the Hoyt L. Sherman Studio Arts Center at Ohio State University. Lichtenstein attended OSU from 1940 until 1949, with a short break between 1943 and 1945 to serve in WWII. During his master's program, Lichtenstein served as Sherman's teaching assistant and Sherman’s scholarship contributed greatly to Lichtenstein’s arrival at his own unique artistic vision.

Sherman pioneered a method of teaching drawing by training the way in which students see and perceive. Sherman's research began with the question of what qualities make art “great” and the idea that pictorial organization, creating a unified and harmonious whole, is the key to making works of greatness. To grasp the ways in which artists accomplish this visual harmony, Sherman spent time examining and analyzing hundreds of “great” works of art. The findings were used to develop a program that integrated the teaching of pictorial organization and the development of a way of seeing in which the whole field is viewed at once and in which all parts of the composition are related to a visual focal point. By practicing and mastering perceptive skills based on “seeing” compositions in scenes and images Sherman believed that even students with no artistic background or talent could learn to draw with skill and ease and be molded into competent draftsmen. Furthermore, harmony in perception would lead to greater harmony in composition and unity in the entire creative act.

Figure 2. Hoyt L. Sherman, Diagram from Drawing by Seeing: A New Development in the Teaching of the Visual Arts Through the Training of Perception (1947)

Sherman’s method involved six twenty-five minute class meetings a week for six weeks in which students drew from hundreds of mostly abstract designs that Sherman developed specially for use in the course. These lessons were conducted in the precisely controlled and measured environment of the Flash Lab, a studio of Sherman's own design where the learning materials were presented in a way that forced students to see and draw in a new way. The Flash Lab was a black room sealed against light with a screen at one end, the instructor with projector and slides at the other end, and in the middle the students on raised platforms to give each an unobstructed view of the screen. (Fig. 2) For the first ten minutes of class time the lights were shut off and students sat, letting their eyes adjust to the darkness as they listened to music and familiarized themselves with the boundaries of their table and newsprint in preparation for drawing in the dark. During each meeting the class was shown twenty slides, each of which was “flashed” for as little as a tenth of a second on the screen, prompting the students to draw the impression and afterimage of what they had just seen. As the course progressed, the students were moved closer to the screens, the slides became more complex and were shown for longer durations and three dimensional arrangements illuminated by strobe lights were introduced.

The “flashing” of pictures on the screen was inspired by a (likely false) anecdote about Rembrandt. As the story goes, a young Rembrandt was looking through a window into his father's windmill and saw a cage of rats inside. However, the interior of the windmill was dark and the cage was only briefly illuminated in flashes of sunlight as the blades of the windmill rotated. Rembrandt's staggered views of the cage were clear, whole images, just as a painter should see each motif he paints. The Flash Lab works quite similarly, flashing the image at such a speed that the human eye is unable to move around the image, identify separate parts of the composition or perceive depth. In this way, Sherman’s approach relies on overcoming these basic instincts of human vision. Sherman sought to promote “monocular” vision with his Flash Lab, helping students to see in terms of relative position, size and brightness and to see the entire image at once and as a “whole.” In addition to emulating great artists, the students essentially behave like “machine[s] that might record nothing but pure visual form.” By suppressing the usual modes of understanding a composition piece-by-piece in favor of viewing things as a whole, Sherman caused his students to see in much the same way as a camera: capturing the whole of a view at once in order to reproduce it.

Lichtenstein himself did not complete a full course in the Flash Lab, but expressed great admiration for Sherman's techniques and often mentioned that he wished he could build a lab of his own. Sherman's teachings stuck with Lichtenstein as he went on to build his artistic repertoire. The canvas, for Lichtenstein, was a place where pieces of the “perceived world” came together to make a composition. He sought unity in each painting and each of his creative acts and pursued a harmonious relationship with the world that he perceived as represented in his art.

Figure 3. Roy Lichtenstein, The Cattle Rustler (1953)

Figure 4. Roy Lichtenstein, Variations #7 (1953)

An implied extension of these ideas of unity and harmony was their role as a reflection of a unified and harmonious culture, which may be why Lichtenstein found subjects in kitschy Americana. Cattle Rustler (Fig. 3), a wood cut from 1953, is a great example of Lichtenstein’s early work that tracks with what we see in Lichtenstein’s Pop Art work. The large, fluid and curved shapes of the horse and rider's bodies are harmonious and move one's eye smoothly around the composition to settle on the focal point of the rider's upper body. The limited palette of light blue, mustard yellow and black also serves to unify all the elements. This abstracted rendering bears similarity to the flattened, simplified forms found in Lichtenstein's later, comic-inspired works.

By 1956 Lichtenstein was beginning to struggle with and deviate from Sherman's teachings. He began to explore “planar dissolution” instead of integration. Variations #7 (1959) (Fig. 4) is typical of this period in Lichtenstein’s artistic career. Color, line, and shape became less controlled and planned as Sherman prescribed and more spontaneous and expressive, giving way to blocks of color and pattern, scribbles, smears and gestural lines. Instead of the playful yet measured shapes and pared-down colors of Cattle Rustler, Variations #7 is chaotic, colorful and almost frantic. The piece’s non-representative abstraction directly challenges the assumed values of artistic and cultural unity that Lichtenstein played with in his Americana work. Color is mixed roughly and directly on the canvas, some lines are jagged and separated while others are smooth and layered together to create blocks of striped pattern. The lack of a definite focal point and the absence of unifying compositional elements creates a fragmented and discordant effect.

Look Mickey!

Lichtenstein's desire to remain faithful to teachings he felt attached to while advanced painting in the art world was taking a completely different direction left him confused and in an artistic funk, but in his desperation he stumbled upon subject matter that would inspire him in a new way. In 1958 Lichtenstein did his very first drawings from pop culture sources. While exercising mark making and Abstract Expressionist techniques, he spontaneously doodled a few images of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck (Figs. 5-6) from memory. Lichtenstein had returned to the Flash Lab, drawing freely and rhythmically what he perceived of the images of Mickey and Donald. Lichtenstein had also then returned to his earlier Americana obsession, as Disney characters, perfectly integrated into every inch of the booming Walt Disney Corporation, became the new symbols of American culture. It would be a short time before Lichtenstein returned to pop culture as a subject for his art, and these sketches planted the seed for his Pop Art success and his return to a focus on seeing and matters of perception.

Figure 5. Roy Lichtenstein, Sketch of Donald Duck (1958)

Figure 6. Roy Lichtenstein, Sketch of Mickey Mouse (1958)

There are several stories surrounding the creation of Lichtenstein's first full-scale Pop Art work, Look Mickey! (1961) (Fig. 7), but all of them suggest that the painting was an experiment that took on a life of its own. In one version of the story, Lichtenstein was discussing art instruction with fellow Rutgers University art teacher Alan Kaprow and he mentioned that it would probably be easier to teach students from cartoons and their pure form than to teach students from complex “fine” artists and this sparked his imagination. In the version of the story most often told by the artist himself, Lichtenstein painted Look Mickey! for his son, Mitchell, whose classmates teased him over his father's seeming inability to draw well after seeing his abstract works. In a presentation in which he discussed his Pop Art works, Lichtenstein said “It occurred to me one day to do something that would appear to be just the same as a comic book illustration without employing the then current symbols of art... I would make marks that would remind one of a real comic strip.”

By the 1960s it seemed that opportunities for creative expression were endless and virtually anything could be a subject or medium for art. However, commercial art and cartooning were still largely seen as low art or not art at all and were unfit for real artistic expression. Look Mickey! was then certainly a breakthrough piece for Lichtenstein as he realized that the only way in which he could put out work of originality would be to do something completely unoriginal and outside the realm of art as he knew it.

Figure 7. Roy Lichtenstein, Look Mickey! (1961)

Figure 8. From Donald Duck: Lost and Found, Illustrated by Bob Grant and Bob Totten (1960)

The artistic choices that Lichtenstein made are interesting because the original illustration that served as inspiration for Look Mickey was not a comic at all. Look Mickey is based on a children’s book illustration (Fig. 8) from the Little Golden Books series. In the original illustration the coloring is not confined to primary colors and the characters are not outlined in comic book fashion. There is also no speech bubble in the original illustration: the exclamation in Lichtenstein's painting is brought in from the text of the book and attributed to Donald by use of a familiar bit of comic book mechanics. Lichtenstein also used the water under the dock to try out using line to express texture and movement as is often done in comic books. Lichtenstein here employs the classic Hoyt Sherman tactic of bringing elements together and manipulating them to create a unified and harmonious whole, which in this case means cobbling together from the text and picture an ideal comic panel, creating a work that is both a comic and a picture of one.

While following Sherman's philosophies on pictorial organization, Lichtenstein also embraces his Sherman-esque interest in seeing and perception. Donald and Mickey have two different perceptions of a single situation. Donald crouches over, expecting to see a fish, but he fails to see the real reason for the tug on his line. Donald also seems to realize the tug on his line, but not the one on his jacket, further dividing his sensory perception. Mickey, on the other hand can see that Donald's line is caught on his shirt tail, and sees that Donald is having a perceptual problem. He stands upright and surveys the scene, snickering to himself.

Context: Comics and Pictorial Media in America

As early as the late 1800s America was acquiring a taste for the pairing of images and words. In popular books such as Mark Twain's The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885) and Howard Pyle's Merry Adventures of Robin Hood (1883) illustrations were being used not only to put into images what had already been said in the text, but to give the reader additional information. For example, In Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, Huck does not give a physical description of himself, so E.W. Kemble's original illustrations established Huckleberry Finn as a young freckle-faced boy in a straw hat and overalls, an iconic image that holds to this day.

Using imagery and writing in tandem to create an integrated whole had great commercial appeal. Newspapers began breaking up their type with occasional illustrations, which made them both more appealing to the eye and more readable with their walls of text being occasionally broken. This led to the inclusion of Sunday supplements including comic strips. As the comic strips became wildly popular, newspapers began to compile comic strips into promotional collections. It was soon thereafter that publishers realized the potential of comic strips as a consumer good. In 1935, National Periodical Publications released More Fun, a periodical consisting of original comic strips and the first modern American comic book. While the new medium had the makings of the artistic and cultural force that we know them to be today, it is important to realize that comics originally were a product of the industrialization of America: the ultimate in quick, cheap commercial entertainment with publishers valuing quantity of titles over quality and speed of creation and manufacture over care for the product.

Early comic books were essentially the synthesis of the ever-popular comic strip and gritty pulp fiction novels, but also present were visual storytelling techniques shared with early film and animation. Comics and film both work with character, dialogue, scene, gesture and compressed time to create a single work of art and so in the early twentieth century the two young art forms shared many devices. Panning to follow action, close-up and cut-in shots to show a character or scene in greater detail, and aerial shots to show expanses of action are just a few of the tactics shared by comics and film. With the popularity of comic strips and moving pictures, audiences became familiar with storytelling based on visual perception.

Americans began to see the world in a new way. Visuals provided stimulation of the imagination that plain words could not, “showing” the story rather than “telling” it and in effect asking the viewer to participate, taking in all aspects and piecing the story together in their own mind. This offered the viewer a new sense of connection and investment in stories “shown” to them through visual means. These new forms of pictorial media also connected audiences by translating ideas and bits of perception into instantly recognizable imagery. It may have taken a writer many lines to describe a complex scene, but capturing said scene in visual means could express this information with much more efficiency. Such efficient transfer of ideas was ideal for an increasingly industrialized and increasingly worldly country. Beyond efficiency, visuals also had the power to convey ideas that simply could not be properly expressed in words.

In the late 1940s America saw a post-war boom in comics featuring stories of crime, horror, war and romance as well as Wild West and cowboy themes. The latter, a return to Western ideas of heroism including heroic myths and folk tales, helped make the new phenomenon of the superhero even more popular. Characters like Superman, created in 1938 by high school students Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, were perfect mythological figures for a new age of technology and industry. The exciting stories coupled with colorful illustrations attracted many young readers, much to the dismay of their parents. A general view of mass culture as dangerous to children combined with a post-war censorship crusade against anything deemed delinquent or un-American launched parents' distaste for comics into the realm of a full-scale moral panic. There was deep suspicion of comics' cultural value as comic book artists and writers were viewed as hacks and their work blamed for promoting juvenile delinquency. Comics were seen as base and stupid but also as possessing a power to be dangerous and destructive. The industry rushed to regulate itself with the Comics Code of 1955, a rigid set of rules for maintaining decency in comic books. The new regulations stifled a once-booming industry and titles, artists and entire publishers began to disappear. Artists and writers were barred from working with even remotely adult material which took down crime, horror and romance titles and solidified the medium's reputation as “kid stuff.” The only comic book publishing houses from this era that survive today are DC Comics (renamed from National Periodical Publications), Marvel Comics and Archie Comics.

At the time that Lichtenstein found himself interested in comics as subjects for painting, there was no doubt a pre-formed idea in his mind of what comics were, as well as an idea of what visual media meant to Americans. Lichtenstein likely approached comics as the product of anonymous artists making adequate drawings to go with trivial and melodramatic subject matter, but also with the realization that they had a certain power over readers. The fact that mass-produced art could have such a strong effect on American culture was an attractive object of study for Lichtenstein. He then sought out comics that fit this image of a mass-produced, vapid and largely anonymous art form, prepared to turn them into experiments in painting and perception.

Context: Lichtenstein and the 1960s Art World

Art had once been the domain of the elite, separated from the general public both metaphorically and physically by museums, galleries and critics, but thanks to the various forms of picture-based media Americans could catch a glimpse of art and artists from the comfort of their own homes. This would be key in the rise of American Pop Art.

Perhaps the most monumental change in American life at this time was the increased presence of television. From the years 1961-1965 around eighty-six percent of American families owned at least one television set and spent an average of 42 hours a week watching it. Television effectively changed Americans’ perception of the entire world. Television was a “window to the world” sitting in the living room. In a world of television, photo magazines and motion pictures Americans more and more frequently found their vision directed through a mechanical device. The prevalence of such technology made seeing in this way second-nature and experiencing the world through the eyes of a camera often could seem as good as “being there,” giving viewers of whatever televised or filmed event a feeling of connectedness and participation.

Americans also found themselves more able to participate in cultural activities. Higher college enrollment made for a public that was more likely to seek out intellectually stimulating forms of entertainment. It was not long before the art community began to take notice of the public's growing interest. The Museum of Modern Art in New York counted a rough tally of some 500,000 visitors from 1960 to 1961, but by the 1968 to 1969 season the museum, now keeping tighter records to keep track of the wild growth of public interest, counted a grand total of 1,033,254 visitors. The American people were less intimidated by art, provoking them to participate in art in little ways like visiting a museum or gallery, enjoying photos of art in periodicals, or viewing a television program about artists. These may seem trivial nowadays but this access to art was new, exciting and even transformative to the American public. However, while art was becoming less daunting Americans were still creatures of habit and gravitated towards familiar subject matter and content. Pop Art employed the ultimate in familiar imagery and as such was poised for popularity.

In 1961 Lichtenstein was working as a professor at Rutgers University in New Jersey and had struck up a friendship with fellow professor and artist Alan Kaprow, who was older and more established than Lichtenstein. Kaprow recognized something special in Lichtenstein and tipped off prestigious gallery owner Leo Castelli to Lichtenstein's work. Ivan Karp, a scout for Castelli, made an appointment to view Lichtenstein's work, and the artist soon arrived at Leo Castelli Gallery in New York with his paintings strapped to the roof of his car. Karp's reaction to Lichtenstein’s work was one of shock and trepidation. “You really can't do this,” Karp said, and went on to describe the comic panel paintings as “Strange, unreasonable, outrageous” to which Lichtenstein replied “Well, I seem to be caught up in it.” Later, Karp would admit to “[getting] chills” from the paintings and being so conflicted about the works that he hid them in a closet for a short time before showing them to Castelli.

Leo Castelli, born in Trieste in the Austo-Hungarian Empire, schooled in Milan, and having spent time in Paris before arriving to the New York art scene, was initially confused by the style and substance of Lichtenstein's paintings. Karp noted that Castelli was not American and thus he did not recognize the clichés and conventions of comics and the cultural conflict created by putting such images to work in fine art in the way that an American would, but he did recognize that Lichtenstein was doing something remarkable. So it was that in 1962 Lichtenstein had his first solo exhibition at Leo Castelli Gallery. There was a certain apprehension on the part of the gallery, unsure how the public would react to Lichtenstein's work. In the year since introducing Lichtenstein's work to Castelli, Karp had been on the receiving end of “a great deal of turmoil [and] very unpleasant moments” while showing people Lichtenstein's work. “People were appalled by them,” he said. However, along with the confusion and shock, there was a curiously charismatic quality to Lichtenstein's work: they were comics, they should have been a total corruption of art, but they displayed expert composition, exact craftsmanship and an unusual je ne sais quoi that made them compelling. Even a professional art dealer like Castelli had trouble articulating just what he saw in Lichtenstein. “It is what you will it to be,” he said in a Newsweek preview of the 1962 exhibition, “one must rise above one's own taste sometimes.” The show sold out completely, each piece fetching prices from $400 up to $1,200.

In October 1962 Sidney Janis gallery in New York held an exhibition entitled The New Realists showcasing Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol, and other American artists working in similar pop-cultural themes. The American works were shown alongside works from artists of the European Nouveau Réalisme including Jean Tinguely and Yves Klein, suggesting that these two groups collectively signified a new era of artistic representation. This show helped to solidify Pop Art as a force in American art and bring together a scattering of artists who, though their individual pursuits and artistic visions, all seemed to arrive at a similar world of ideas about art and culture while staying mostly independent, socially and artistically, from each other.

Figure 9. Richard Hamilton, Just What Is It That Makes Today's Homes So Different, So Appealing (1956)

These new Pop Artists were not the British Pop Artists, who had similar subject matter but were a completely separate and different artistic movement that had been in process since 1949. Critic Lawrence Alloway had coined the term “Pop Art” to describe the movement and defined the title as “the use of popular art sources by fine artists: movie stills, science fiction, advertisements, game boards, heroes of the mass media.” British Pop Art had been more explicitly theory-based across the board and had a somewhat foreboding tone, displaying the trappings of American commercialism in an almost grotesque manner. The hallmark of British Pop Art is Richard Hamilton’s collage Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing (1956) (Fig. 9), which was originally intended as a poster and catalogue illustration for the 1956 exhibition This Is Tomorrow. Taking its collage material from advertisements to create a scene of domestic life addled by bizarre product placement, Today’s Homes characterizes British Pop Art, whose artists often concerned themselves with the invasion of everyday life and the home by popular culture and consumerism. The new American Pop Artists like Lichtenstein appealed to a “lighthearted American pragmatism” and approached their subject matter with an irreverence, or sometimes such a reverence that it seemed to come full-circle back to parody, that challenged art more than it challenged the popular culture from which it borrowed. But while art was being challenged in the Sidney Janis gallery, these Pop Artists were certainly not anti-art and despite critical claims to the contrary, were not reviving Dada, which exhibited a far greater sense of hostility and violence in and towards the creative act as well as society. Indeed, these artists were the New Realists, drawing inspiration from the twentieth century environment that they inhabited every day and from the images and objects around them. Just as earlier painters had used the trappings of their lives as subject matter, Roy Lichtenstein painted such modern paraphernalia as aerosol cans, washing machines and, of course, comics.

Critical responses to the show varied and were peppered with backhanded compliments and biting commentary on the perceived artistic value of pieces at the show, the artists being shown, and Pop Art in general. In previous years critics had expected that the next major trend in American art after Abstract Expressionism would be a return to figuration and recognizable subject matter, which is funny because Pop Art accidentally called that bluff. Critics seemed to think that Pop Art was picking far too recognizable subject matter. Many critics stopped just short of calling Pop Art a gimmick and its artists hacks. Brian O'Doherty of the New York Times summed up The New Realists as a “satiric attack on Madison Avenue... America has been a pioneer in throwaway cups and saucers, milk containers and tablecloths. Now it is a pioneer in throwaway art.” Time magazine christened the new artists the “Slice of Cake School” because of their fascination with supermarket items. Probably the most scathing comments came from Thomas Hess of Art News, whose tirade against the show singled-out Lichtenstein, saying that he was “falling for the banal...doing it about like Norman Rockwell.” He called the show “nothing particularly new” and “eminently writeable-about, as against the Abstract Expressionists whose masterpieces convince you at non-verbal levels.”

The Abstract Expressionists were a continual point of comparison for Pop Art, having been the gods of American art in years past, and most critics and artists saw Pop Art as a cheapening of American art instead of a new and exciting continuation of American artistic expression. The artists of the Abstract Expressionist considered themselves a movement, and so they were hostile as a group towards the new Pop Artists. The Abstract expressionists collectively, save for Willem deKooning, left Sidney Janis gallery as payback for holding the New Realists show. But while it is easy to see why these artists were reluctant to give up their spot at the top of the art world pyramid, it is obvious that these artists and critics were set in their ways and wrapped up in their presumptions. The Abstract Expressionists' pursuit of new and avant-garde ideas and their willingness to experiment and push the boundaries of art created the environment in which these new Pop Artists' work could be created and shown as art. With seemingly haphazard splatters of paint being considered art of distinction, it was not too far a leap to consider the comic strip or celebrity portrait as a viable and meaningful subject for artistic exploration. This is not to suggest that Pop Art or its artists aimed to attack or mock Abstract Expressionism, but in some ways Pop Art was exposing the arbitrary cultural hierarchy that held Abstract Expressionism aloft, calling attention to the way in which “high art” is separated from mass culture, even in the case of Pop Art where the two are nearly identical products. Pop Art was part of the long-running pattern of new artists rejecting the old standards while building their own, just as the Abstract Expressionists had been.

The public was captivated by this new, fun art that used familiar imagery and was amusing and engaging as well as meaningful. Pop Art also had a youthful swing to it that attracted the young and those who wished to be young again. Abstract Expressionism's philosophical and introspective subject matter seemed heavy-handed and even passé in comparison to this new art that reflected and reveled in the world outside the gallery or artist's studio. The outside world was invited into the artist’s studio in magazines and on television. Years before, America was confronted with Jackson Pollock, a distant and dark character creating art that was lauded by critics but to which many “normal” Americans could not relate in the slightest. Roy Lichtenstein, however, was a jovial college professor who created work with which Americans could easily connect in terms of subject matter, and in terms of its availability to be viewed in person and via mass media. An article in Esquire magazine summed up the situation, explaining that Pollock personified “the romantic artists, the life burned out, the garret” whereas Lichtenstein “puts art on, sees no terror in humor, has no values.”

Lichtenstein’s Pop Art Technique

Lichtenstein’s, or any Pop artist’s, place within Pop Art cannot really be qualified in terms of relationships to other artists or to critics or adherence to theories or practices. Pop Art was at best a loose confederation of artists, critics, and personalities all engaged in their own pursuits and occasionally crossing paths. There was no unifying theory of American Pop Art, no singular manifesto or ultimate championing critic. Before we get to the theory, we will take a close look at Lichtenstein’s artistic process and the material qualities of his comic panel paintings, for these are integral to his artistic vision and any theoretical discussions that might arise. As Lichtenstein experimented with Pop Art he developed his own way of manipulating materials and his own ideas as far as artistic vision and theory.

For Lichtenstein, picking source material was not haphazard, nor could it have been anything less than a calculated effort to construct a perfect composition. Lichtenstein appears to have made a conscious effort to locate comic books to use as sources. The comic books that Lichtenstein used date mainly from the early 1960s, which shows that he was not employing comic books that belonged to his sons or that he had collected previously.

Figure 10. DC Comics, Secret Hearts #82 (1962)

Figure 11. DC Comics, Our Fighting Forces #52

The majority of Lichtenstein's comic panel paintings have their origins in romance stories and tales of action and adventure, commonly referred to as “love comics” and “war comics” with titles like Secret Hearts (Fig. 10), Our Fighting Forces (Fig. 11), Girls' Romances and GI Combat. These broad genres were cash cows for comic publishers and love comics in particular were the single most popular genre in comic books from 1947 to 1965, making them the ultimate in easy, profitable mass-market entertainment. These genres had their own conventions in art, writing and the manipulation of the elements of comic book storytelling that may have attracted Lichtenstein.

In love comics the stories were melodramatic, formulaic and devoid of any overt experimentation in writing or illustration. The characters were also formulaic and lacked strong, recognizable personalities or distinguishing looks, which allowed readers ease in identifying with the characters. For Lichtenstein's purposes, these every-men and every-women were anonymous figures with no baggage or expectations attached to them who were easily manipulated into their place in the unified composition of the comic panel paintings. Love comics were also an ideal choice for Pop Art works because of their attachment to popular culture at large. The artists who worked on love comics had a special interest in popular fashion and culture, giving their characters current and popular hairstyles, clothing, cars and other amenities of modern youth culture, firmly grounding their work in the same popular culture that provided advertising images for Lichtenstein's later consumer-product-based Pop Art works. By deliberately picking these relatively generic and overexposed sorts of comics as source material, Lichtenstein had room to mold them.

A love comic served as the source for Ohh…Alright…(1964) (Fig. 12). A girl with short red hair holds a telephone receiver up to her ear, scowling slightly. Her speech bubble reads “OHHH… ALRIGHT…” The woman is young, pretty and unspecific and her surroundings and situation are unknown. Her dialogue is dreamy, as is much dialogue in love comics because of the emotional focus of the stories, but Lichtenstein has also left it deliberately vague within the situation. Because love comics were really the only sort of comics that featured young, “normal” girls in such situations, viewers are prompted to assume that the context of the panel is within a story involving romantic relationships and the related emotions.

Figure 12. Roy Lichtenstein, Ohh…Alright…(1964)

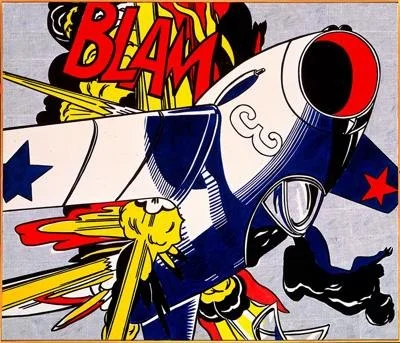

War comics obviously contained much more visual action than love comics due to their subject matter. Lichtenstein’s paintings that were based on war comics were often done on much larger canvases than the love comics-based paintings. They evoke frames from action movies or tv shows, reinforced by the big screen scale of the paintings. Onomatopoeic words like “WHAM!” and “BLAM!” add a sense of excitement and urgency, and are used as design elements in their own right. In the comic narrative, the onomatopoeia often serve as a linking element between panels or scenes of action. Characters also speak in short, punchy statements, barking orders or shouting interjections. These urgent statements and sound effects indicate the instantaneous time span of the moment. These frozen moments isolated from the fast paced action of their stories create a different type of ambiguity from love comics' vague and dreamy language.

BLAM (1962) (Fig. 13) is based on a panel from DC Comics' All American Men of War #89. The busy, almost frantic panel shows an airplane upside down and exploding in flight while the pilot drops from the cockpit. The explosion emits the titular onomatopoeia “BLAM” in bright red block letters along with smoke and fire. The painting is quite large at 68x80 inches, and a viewer standing in front of it would seem to be engulfed by the color and action of this frozen moment. What might look like exciting action on a television or movie screen from across the room becomes more menacing the closer the viewer is, evoking the difference between experiencing war via media and experiencing war by being there, up close and personal. On a darker note, when taking up most of the viewers visual field the painting also evokes a frozen memory of combat, even a post-traumatic flashback.

Figure 13. Roy Lichtenstein, BLAM (1962)

In picking these comic genres as source material, Lichtenstein actively avoided other sorts of comics. By the 1960s, comics experiencing a renaissance of superhero activity, what is now called the “Silver Age” of superhero adventure comics and is notorious for its over-the-top-ness. At the same time, Marvel comics' new focus on misfits and reluctant superheroes attracted the young college-age avant-garde and drug cultures with stories of normal people with fantastic powers as well as richly illustrated and often psychedelic artwork. Underground comics from small publishers unencumbered by the Comics Code also pushed the boundaries of storytelling, art and good taste, creating very edgy, emotional and turbulent works. Lichtenstein, while hypothetically browsing the comic book racks at his store of choice, made a decision to avoid these new offerings for several reasons. These comics had recognizable and iconic characters about which the public had already formed images and opinions, making them unsuitable for his brand of Pop Art, which focused on the impersonality of mass-produced products. The more ambitious comic works also contained far more personal style in terms of illustration as well as far more personal input and creativity in writing, as opposed to the relatively direct worlds that love and war comics worked within. Perhaps most significantly, these works did not reflect popular culture in the same way as love comics and war comics and instead catered to specific types of readers. By sticking to material meant for a near-universal audience and bereft of any readily apparent artistic value or personality Lichtenstein was free to cobble together comic images that fulfilled an ideal, popular image of what comics were.

After choosing comics to pull from, Lichtenstein would search the books for panels, figures and words that sparked his interest. Lichtenstein owned piles and piles of books often with only one or two elements extracted from the book by scissor to be taken to the drawing board. The extraction could go one of two ways: The direct appropriation of an entire panel that would then be manipulated to Lichtenstein's content, or the assemblage of an entirely new and deceptively authentic panel from several elements such as independent figures, speech balloons and scenes. Cold Shoulder (1963) (Fig. 14) is one of Lichtenstein’s paintings that was constructed from various sources. The speech bubble, dripping with icicles to represent a chilly disposition, came from a panel of a love comic in which a woman begrudgingly greets her love rival. The image of the girl with her back to us comes from a love comic in which a girl is turning away from and leaving her lover. The two elements were brought together by Lichtenstein on one panel, creating a strange situation in which the text and image are contradictory: a woman speaking a greeting, but with her back turned.

Figure 14. Roy Lichtenstein, Cold Shoulder (1963)

After several hand-drawn and planned trials of the ways in which the panel could be finessed, the chosen elements were refined for compositional unity including color choice throughout the panel, word choice in speech balloons and often an omission of superfluous illustration in scenery and distinctive marks in face or clothing meant for character definition. A complete drawing was then made from the revised source material, often with subsequent revisions to get everything just-so. Lichtenstein then projected the finalized image onto canvas where it was traced by hand. The image was then painted with flat color, black line and other necessary graphic elements. An often included element that served to underscore the manufactured nature of the original printed material were Ben-Day Dots (Fig. 15), invented near the beginning of the 1900’s by American printer Benjamin Day, who used clusters of dots to create shaded or tinted areas while printing using techniques that did not allow for gradients or color mixing. Many of these more mechanical steps such as tracing lines onto canvas and painting Ben-day dots were done with the help of assistants to cut down on the time spent on the painstakingly precise compositions, but these assistants were kept solely for these practical reasons and did not factor in to the artistic considerations of Lichtenstein’s work.

Figure 15. An image from a newspaper showing shaded areas made up of Ben-Day dots.

This method was a by-hand replication of the mechanically printed and replicated source material, turning Lichtenstein himself into a machine performing the act of replication. The method highlights the tension between the mechanical and the handmade. While Lichtenstein had left Abstract Expressionism and painterly mark making techniques behind, he retained an attachment and allegiance to the medium of painting. Basically, Lichtenstein removed his painterly hand from his pop art work by using his expert painterly techniques. Just as Pop Art as a whole challenged existing ideas of what art could be, the way in which the comic panel paintings are “mechanically handmade” challenges the viewer’s perception of how art is, or should be, made.

Mechanical Reproduction: Warhol/Lichtenstein

Television played an integral role in the shaping of 1960s culture, and it also enabled the art and artists of the 1960s to be more visible than ever. The use of new technologies in portable cameras and equipment encouraged filming excursions beyond the soundstage, and the interview format was an increasingly popular approach. During primetime on Tuesday, March 6, 1966, WNET aired an edition of their weekly series USA: Artists entitled Warhol/Lichtenstein.

The first half of the program focuses on Lichtenstein: cool and collected and speaking of the aims of his art. Lichtenstein explains himself using terminology like “anti-sensibility painting” to describe his work, and it seems that he is completely in control of his art and ideas. On the other hand, Warhol, highlighted in the second half, is a deliberately vexing subject. Warhol denies being made a passive subject of the documentary by refusing to answer questions, allowing moments of awkward silence, and asking what the director “wants” him to say, putting the interview in the spotlight instead of his art. Warhol’s invasion of the interviewer’s space bears resemblance to the way in which his works exist as objects that seem to enter our space instead of inviting us to enter theirs. These interviews exemplify Lichtenstein’s thoughtfulness and methodological approach to art versus Warhol’s insistence on becoming an object of consideration himself. While Lichtenstein aimed to create art of meaning, Warhol aimed to be his art by affixing meaning to himself and his art in kind.

When the matter of Lichtenstein and Warhol’s shared affinity for aspects of mechanical reproduction is considered, this creates an interesting comparison. Warhol mechanically reproduced his works by silkscreen, often delegating major steps of production to friends and assistants and effectively removing his hand, or any artist’s hand, from the work. Warhol himself had said that he chose silkscreen for its “assembly-line” effect, connecting his work to the process used commercially to print designs in smooth, flat color on labels and boxes. But while Warhol’s hand is largely absent from the creation of his work, he actively sought out subjects with personal meaning to him such as his favorite Campbell’s soup and celebrities he admired. Thus, Warhol has an intensely personal connection to work from which his hand is completely removed. Meanwhile, Lichtenstein detaches himself personally from his work while remaining dedicated to painting, using his own hand to create a semblance of mechanical reproduction. Lichtenstein never seemed to express any real affinity for comic art or consumer products beyond their use as subjects for art that ultimately was not really about the objects themselves.

Warhol and Lichtenstein also diverge in their treatment of branding and recognition in pop culture. Lichtenstein removed symbols and indications of specific brands or persons from his work, emphasizing the anonymous universality of these people or objects. Warhol obsessed over brand and recognizable celebrity, which simultaneously addressed his personal infatuation with such things and the admiration that society as a whole has for these commodities. Both of these approaches address aspects of the mass-produced in popular culture that unite all that fall under its spell.

Transience: Rosenquist/Lichtenstein

Like Lichtenstein, Pop Artist James Rosenquist experimented with gestural and abstract works before arriving at Pop Art sometime between 1960 and 1961. He began to construct paintings on a monumental scale, appropriating images from print media and applying techniques he learned while taking jobs painting billboards to support himself and his art. The images used in Rosenquist’s pop works are varied: sections of automobiles, food, human faces, words taken out of context, often all at once. These images are what one might see separately on various roadside advertisements or on pages of a magazine, but in his works Rosenquist has synthesized and assembled them into new compositions. While Lichtenstein collects and assembles elements from comic books into ideal comic compositions, Rosenquist’s compositions are not idealized and instead show these elements coming together to create chaotic and even hostile scenes.

Both the truncated and reassembled images and symbols of Rosenquist’s work and the isolated comic panels of Lichtenstein’s are essentially fragments of reality. The objects in these artists’ works are seen for a fleeting moment from a car window or skimmed past while reading, and both artists seek to fix these momentary glimpses in place so that we might consider them thoughtfully. These two artists engage an often overlooked facet of Pop Art: transience, change and impermanence. The images that Rosenquist and Lichtenstein borrow from print media are, in their original forms, exceedingly easy to dispose of and often discarded quickly after reading.

Figure 16. James Rosenquist, The Light That Won’t Fail I (1961)

Works from Rosenquist and Lichtenstein highlight the enigmatic nature that transient, disposable, forgettable images can take on. The fragmentation and juxtaposition of images in Rosenquist’s work creates an atmosphere of ambiguity, a quality which is also a decided goal of Lichtenstein’s in his isolation of individual comic panels. In The Light That Won’t Fail I (1961) (Fig. 16) Rosenquist brings together disparate images from advertising. An image of a woman exhaling smoke and holding a cigarette is overlaid with a rendering of a comb and another image of the hands and feet of a male in the action of putting on socks. The source images, painted smoothly and in monumental size by Rosenquist’s skilled hand, are heavily cropped and in divergent scale to one another but ultimately make up a strangely harmonious composition. These fragments pieced together on the same picture plane may suggest various situations (a post-coital moment, for example) but there is no definitive reading or message to be found and viewers are left to interpret and respond to the piece however they please. Lichtenstein and Rosenquist find commonality in the open-ended qualities of their work and the way in which viewers are offered an opportunity to perceive the painting in their own individual way.

Ways of Seeing: Ruscha/Lichtenstein

Lichtenstein and Los Angeles Pop Artist Ed Ruscha engage in approaches that show very different aspects of American popular culture, but both were experimenting with similar ideas about the ways in which popular culture changes the way we see. Both Lichtenstein and Ruscha's art depict the original object manipulated to create dramatic compositional strategies which provoke new ways of looking. Though normally separated by thousands of miles the two were not strangers. In 1962 on his way back to his home in Los Angeles after a car trip through Europe, Pop Artist Ed Ruscha stopped in New York and saw examples of Lichtenstein’s Pop Art work at Leo Castelli gallery. Lichtenstein and Ruscha also crossed paths on Ruscha’s turf when both artists were featured in the “New Paintings of Common Objects” show at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1962.

Ruscha broke through with his monumental depictions commercialism, such as corporate architecture and larger-than-life logos. The viewpoints taken in Ruscha’s paintings of buildings, most famously gas stations, have been likened to views from a speeding automobile. This way of seeing is a symbol of the lifestyle and experience of the urban sprawl of Los Angeles. Ruscha's works also nod to the idea of the billboard, a visible and prevalent piece of pop iconography that conveys a clear, simple and graphic message to the public.

Actual Size (1962) (Fig. 17), one of Ruscha’s billboard-inspired works, contains some interesting ideas in terms of perception and the act of being a viewer or spectator. The top portion of a large canvas is painted an unsteady deep blue, rich with brushstrokes. This blue paint drips onto the bottom portion which remains mostly white, a reference to carelessness on the part of the billboard painter that Ruscha is embodying. On top of the dark blue field is written “SPAM” in fat yellow letters, in the fashion of the logo of the canned meat product. The separation between the blue and white portions is almost evocative of a horizon line, making the blue portion with the added lettering almost like a simplified representation of a billboard on the horizon, replacing the sky. In the white portion, a life-size rendering of an actual can of Spam seems to be falling, emitting a yellow streak behind it like the tail of a comet. Upon the yellow streak is softly written in graphite pencil: “ACTUAL SIZE.”

Figure 17. Ed Ruscha, Actual Size (1962)

Like Lichtenstein, Ruscha toys with the ways in which the painting is connected to the original object as well as the “real world.” Actual Size prompts the spectator to question whether the painting is indeed about the world, and if it does actually contain pieces of the material world, “actual size.” The painting is “actual size” in and of itself because it is a physical object, but the images depicted are questionable: Is the titanic logo representing the concept and brand of Spam “actual size?” Is the flat reproduction of the single can that one would find in a supermarket truly “actual size?” Which object is more real and which scale is, in fact, the “actual size” of Spam?

In Actual Size, a viewer must engage in two very different and nearly disconnected modes of “looking” to see the whole painting: distanced observation by which one can see the entire field, and close viewing to examine the details including the “actual size” can of Spam. In both Ruscha’s and Lichtenstein’s work there is use of pictorial space that makes one consider the work of art both as an object and a depiction of another object.

By using familiar objects Lichtenstein and Ruscha ask their viewers to consider their relationship not only to the painting, but to the original objects: Do these paintings seek to use simple forms to convey a simple message in the same manner as the original object, or are they more complex and deserving of closer examination? In much the same way that Lichtenstein's comic panel paintings are of an idealized comic art, to the point of becoming a depiction of the very idea of what comics are, Ruscha's building and billboard pieces do not represent actual places or things as much as they represent idealized images associated with Los Angeles, or ideas of what Los Angeles is.

Seeing Lichtenstein’s Comic Book Paintings

“My work isn't about form. It's about seeing. I'm excited about seeing things, and I'm interested in the way I think other people saw things.”

Lichtenstein's redefinition of what art could be was less a matter of putting cartoons and objects of “low” culture on display, and more a manipulation of our perceptive habits by using form abstracted in the manner of the common cartoon to manipulate the way we see and perceive. Lichtenstein’s paintings of comic panels are perfect for this perceptive scrambling because as Scott McCloud says in his essential text Understanding Comics: cartooning is, in and of itself, a way of seeing. During his explosive success in New York, Lichtenstein must have realized that just as Look Mickey! had held a power over him and his creative vision, his comic book subject matter had a power over viewers. Lichtenstein's work had succeeded in not only isolating the ideals of the comic book style, but teasing out the visual and narrative mechanisms that make comics an engaging and attractive form of mass entertainment. While being stand-alone works of art, Lichtenstein’s paintings continue to refer to the comic book context even while being removed from it.

Lichtenstein uses abstraction to create expression, which is a familiar concept in fine art, but the manner in which Lichtenstein uses abstraction through cartooning is more in step with “low” art than fine art. This approach is summed up by McCloud as “amplification through simplification.” The basis of this view is that ideas become more emphatic the more easily they are perceived. The abstraction that comic book illustrators practice, cartooning, does not eliminate detail as much as it focuses on specific details for the purpose of getting across the maximum amount of information using minimal design elements. Illustrations in love and war comics use drastically simplified depictions of men and women, often with one or two specific details to denote them as individuals within the story but not enough to set them apart from the world at large. These characters then easily serve as vessels for the story at hand, without marring the simple plot points and emotional scenes with their individuality. Again from McCloud: downplaying the appearance of the physical world in favor of the impression of what the world looks like puts comic book illustration in the “world of ideas,” giving it an uncanny ability to nurture a fluid connection with the viewer or reader. Lichtenstein’s melodramatic comic panels use the flatness of the picture plane to convey moments of simple emotion and heightened tension, not unlike the dramatic close-up of mawkish cinema, and the plane becomes a cut-out piece of a larger narrative or scene that the viewer is denied and at which they can only guess.

Figure 18. Roy Lichtenstein, Drowning Girl (1963)

Drowning Girl (1963) (Fig. 18) is a perfect example of this flattened, simplified reality that shows emotion divorced from context. The square canvas provides a close-up of a girl submerged in rushing waves of water. Around her are wild, organic lines and shapes of flat dark blue and bluish-white, indicating the closing of the waves around her. As tears leak from her eyes, a thought bubble pops over her head, reading “I DON’T CARE! I’D RATHER SINK THAN CALL BRAD FOR HELP!” In his use of flat color, a unified, centralized composition and a “bird’s eye” viewpoint of the scene, we are shown a world of surfaces with flattened space and little depth, making the expression and drama all the more immediate.

Another important element of the comic narrative that McCloud cites in Understanding Comics is that of closure, a psychological term which he concisely defines as “seeing the parts, but perceiving the whole.” Closure is a part of daily human life in which we use clues, cues, and our past experiences to infer basic things about the world and situations in which we may find ourselves. Automatic mental closure is also what allows us to perceive moving pictures from rapidly flashing sequences of images projected on a screen. Closure is also what students engaged in while attempting to draw something they had just barely seen in Hoyt Sherman's Flash Lab. Comics use closure as their primary means of conveying time and motion to readers and closure is manipulated by the comic book artist in several different ways.

While hanging on a gallery wall, Lichtenstein's paintings are surrounded by space that would be the “gutter” between panels in a traditional comic strip. This realization is easy to overlook, but it holds tremendous power in terms of the way in which one perceives a Lichtenstein comic panel painting. In a sequential format, a comic artist can manipulate space between panels, each of which is treated as a moment in time, to effectively manipulate the reader's perception of the passage of time between events. Less space between panels creates a sense of quickness, speed and even urgency, while more space between panels simulates a longer passage of time, and feelings of lingering or contemplation. A panel without dialogue that offers no clues to how long it is meant to last can produce a sense of timelessness. Lichtenstein’s paintings can go both ways: some contain snippets of dialogue giving them immediacy and impact, though often the text refers to a continued or ongoing thought with the use of ambiguous language as well as typographical cues like ellipses. Some panels contain no words at all, capturing a lingering moment of stillness and contemplation. Paintings such as Blond Waiting (1964) (Fig. 19) use the conventions of the comic narrative to construct moments removed from time. The scene is without any indications of movement and one would not expect any: a woman with flowing blonde hair lies with arms crossed, looking at a clock. While implying stillness, the painting also does not give any clues to how long this scene will last. Because there are no clues to indicate passage of time, this moment can seem to be timeless or everlasting.

Figure 19. Roy Lichtenstein, Blond Waiting (1964)

Figure 20. Roy Lichtenstein, Torpedo Los! (1963)

Paneling to communicate time and motion in comics also relies on how much, or how little, information is given to the reader both between and within panels. A comic panel removed from sequence means that the viewer no longer has access to the context: characters perform actions without prompting, the scene is only partially visible and portions are entirely left out, references are made to inaccessible objects and events. In some ways this can be jarring, but it also prompts viewers to engage in closure and make inferences as to what exists outside the bounds of the panel they are given. A painting such as Torpedo Los! (1963) (Fig. 20) is constructed to be a quick moment, with the implications of a quickly shouted order and the urgency of the wartime scene. The scene shows an extreme close-up of a submarine captain at a periscope. His speech bubble reads “TORPEDO… LOS!” with the latter word written in red block letters to indicate emphasis. A second man stands behind him, implicitly taking his orders. Torpedo Los shows a scene of action, but there are no clues to what exactly is going on.

In a typical comic panel sequence, closure serves to link panels together. Often this is simple, such as a character holding a glass in one panel and drinking from a glass in the next: the character lifted the glass to his lips. However, by leaving out more information between panels an author can force a reader to create more of the story in his or her mind using clues and cues from panel to panel. As the space between panels becomes larger or signifies a greater “jump” through time readers must use more of their imaginations to fill in the blanks. Completely separated from their narratives, removed from time and motion, but inexorably tied to the comic mode of perception, Lichtenstein’s comic panels have endless possibilities for viewers’ engagement and interpretation.

The comic panels on a blank wall, grouped together with and adjacent to other works of art also nod to the idea of the gallery or museum establishing its own panel-by-panel narrative, not unlike that of a comic strip. Curators carefully select and arrange paintings, hanging them on walls to create a desired flow through the gallery and a unique experience for patrons. The experience of each painting is informed by the others around it, and often a specific narrative is presented. In the New Realists show, for example, works from the American Pop Artists were presented alongside works from the European Nouveau Réalisme in such a way that implied that the roots of Pop Art could be traced to ideas displayed by these European artists. Curators can manipulate space between panels in much the same way as a comic book artist, crowding paintings together to show a certain rhythm or relationship or staggering them to provide moments of clear contemplation. When presented at once and near each other, groups of Lichtenstein’s comic panel paintings can take on the nature of a flock of overwhelming commercial objects but one work of that same group, alone on a wall, can be an object of meditative study.

A viewer who has seen a cartoon or comic before, no doubt a vast majority of Americans, is familiar with and naturally capable of the process of fed information and closure necessary to reading a sequential pictorial narrative. A viewer looks at a Lichtenstein comic panel painting, jarringly removed from its context, and immediately engages in the closure expected of a comic reader. Simply by being comic images they invite viewers to do more than passively view the colors and forms. Lichtenstein is not only seeking to play with viewers’ perceptions of his art or art in general but how viewers’ perception can be manipulated and informed by extraneous forces, seen or unseen. Lichtenstein is changing the viewer’s way of looking at the medium of painting by loading it with the tricks of a completely different and very specific art form, and this is made possible because of comics’ role in America’s visual culture. This elaborate setup only to show images that could be found at a drugstore shows the ways in which visual culture and mass media have changed the ways in which we see and perceive.

Conclusion

Lichtenstein's comic panel paintings are characterized by tension between the popular and the avant-garde, between the handmade and the mechanically reproduced, and between what can be seen and what can only be perceived. This puts his art at the intersection of these specific ideas, but in a larger sense, the comic panel paintings sit at the crossroad of American culture and Lichtenstein's personal artistic vision, making them remarkably successful works in both spheres.

While various circumstances and cultural shifts often push comics to the fringes of what is considered “art,” they remain a force in American culture. Lichtenstein’s use of the language of the common comic book as a vehicle for more “serious” artistic ideas grounds his work in American culture and separates it from more traditional and international ideas in art. Lichtenstein painted an aspect of the American environment that cut to the core of American industrialized life, embracing an art form that evolved from and because of the directions that America took technologically and culturally.

The comic panel paintings have provoked strong responses in the general public largely because of their comic nature. Reactions that viewers have to the bits of narrative and anonymity of the figures promote a connection and affinity to the work, and because of comics' historical relegation to youth culture they evoke an attractive youthfulness and whimsy. They are easy to quantify in terms of subject matter, often somewhat humorous or satirical and generally fun to enjoy as works of art. These qualities then made Lichtenstein’s work ripe for re-admittance into popular culture, making his art as ubiquitous and profitable as its mass-produced origins.

Lichtenstein’s work is also tied to American fine art heritage and practice. Lichtenstein was part of the first generation of American artists to be professionally educated in art, in design, and in technical skills, and to have these subjects taught in an American environment. Lichtenstein and artists like him were introduced to artistic concepts through the tutorship of other American artists, teaching from an American point of view. Lichtenstein's attendance at Ohio State University, one of the first American universities to offer a comprehensive art degree, introduced him to Hoyt L. Sherman’s ideas on perception as the underpinning of successful art. Lichtenstein’s dedication to Sherman’s methods even brought him to the unspoken conclusion that harmonious art came from harmonious culture: in this case, twentieth century American popular culture.

Along with twentieth century American culture comes a particular way of looking at the world, informed by industrial pictorial media. America was introduced to photos in print and moving pictures on screen fairly early in its history as a country. These things were easily assumed into American culture, and their availability was unparalleled. Americans saw Lichtenstein’s art and immediately identified with it because its imagery was part of their everyday lives and ultimately their cultural heritage. The perceptual experiments at play in Lichtenstein’s work rely on this mode of viewing the world through the lens of popular media, on the assumption that comic imagery has its place in a narrative and on the feeling of experiencing the world through pictures. Lichtenstein married his own artistic interest in vision and perception in art with the mechanics and symbolism of a mass-produced but distinctly American art form, using tools available to him because of his American experience. Just as the images he appropriated came together to symbolize American life and industrialized consumer culture, all these aspects coming together at once made Lichtenstein and his works symbols of Pop and American art.

Adapted from my undergraduate thesis in art history

Published 2011 at Loyola University Chicago

Advised by Dr. Marilyn Dunn and Dr. Paula Wisotzki

Full bibliography and original text with citations available upon request.

Selected Sources

Drawing by Seeing: A New Development in the Teaching of the Visual Arts Through the Training of Perception, by Hoyt L. Sherman (1947)

Image Duplicator: Roy Lichtenstein and the Emergence of Pop Art, by Michael Lobel (2002)

Roy Lichtenstein, edited by Graham Bader (2009)

The Pop! Revolution: How an Unlikely Concatenation of Artists, Aficionados, Businessmen, Collectors, Critics, Curators, Dealers, and Hangers-on Radically Transformed the Art World, by Alice Goldfarb Marquis (2010)

Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, by Scott McCloud (1994)

Image Sources

Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20